Learning

the Secrets of the Steps

THE

HIDDEN WORLD OF FORECLOSURE AUCTIONS AT 360 ADAMS STREET

UNDERNEATH

THE steel-and-cement over-hang of the Brooklyn Court building

on Adams Street, on practically any weekday morning, a crowd gathers

on the steps of the court- house to buy foreclosed Kings County

properties.

UNDERNEATH

THE steel-and-cement over-hang of the Brooklyn Court building

on Adams Street, on practically any weekday morning, a crowd gathers

on the steps of the court- house to buy foreclosed Kings County

properties.

Here's how it works: A house is purchased in Brooklyn with bank

financing. The owner, for whatever reason-loss of a job, divorce,

bad tenants-stops making mortgage payments. The bank decides to

foreclose on the house. A civil action is commenced in Supreme

Court by the bank to reclaim the property. Most cases go uncontested

(if strapped homeowners can't make mortgage payments, they probably

can't spare a few thousand for a lawyer). The bank gets a Judgement

of Foreclosure signed by a Supreme Court Justice, but the bankers

don't want the house; they want their money back. So they auction

it off.

About

2,000 Brooklyn homes change hands this way each year. The bank

runs a notice for a few weeks in a local paper announcing that

the property will be sold at a public auction to the highest bidder

on the steps of the courthouse. And that's where the regulars

come in.

"It's

not as easy as it looks. These auctions can get pretty fierce,

and you have to know what you're doing," says Mickey Higgins,

54, who works as a paralegal for Nationwide Court Services and

goes daily to the auctions representing the plaintiff in the action,

the bank.

"Every

other month we get people who have seen some T.V. commercial on

how to make a fortune in foreclosed properties. They think they

are giving homes away out here. First, you need 10 percent of

the sale price in either cash or certified check that day. If

you make a bid and don’t have the money, the referee comes

right back out and starts the bidding again. Secondly, most times

you don't know what shape the house is in, so you don't know what

you're really buying. And if the house has nonpaying tenants,

they become your nonpaying tenants, and it will take a year to

get rid of them. It's a tough racket for the single home buyer."

Higgins,

from Bay Ridge, has an easy way about him, and is happy to break

down the mysteries of public auctions. His only job is to make

sure the bank gets its money. He knows the bank's upset price

(the minimum they will take) and makes sure that the number is

reached.

"I'll

let all the bidders know we are starting the bidding at, say,

$100, but my upset price is $131,000, so they might as well go

from there."

The

auctions are run by "referees," impartial lawyers who earn $500

a sale for reading the terms of the auction, checking in bidders,

making the auction call and handling the transaction between the

plaintiff and the buyer.

Higgins

explains how the regulars have developed a system to keep the

public confused. "You'll see ten people in front of me and the

referee, but there's only three bidding. They bring extra people

in for diversion. There are three main factions out here--two

groups of Hasidim and one of real estate brokers. Sometimes they

work together and sometimes they work against each other.

"The

real estate guys really just want to sell mortgages," Higgins

explains. "If they buy the property they try to sign it over to

another guy and make a quick profit."

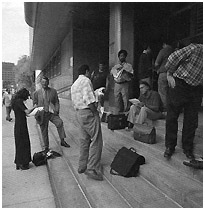

ON

THE COURTHOUSE STEPS, ABOUT 15 men and women stand around nervously

talking and squinting in the morning sun. A few lean against the

courthouse wall, eyeing newcomers. One man grips the rolled-up

sheet of paper that is the public auction bible-the

Brooklyn Foreclosure Auction Schedule-known colloquially

as the "Yellow Sheet" put out weekly for the last 10 years by

Profiles Publications, Inc. in Jackson Heights, Queens

(www.nyforeclosures.com).

The 10-page bulletin gives the listings of the auctions going

on in any given county, and some background information on the

properties. The people getting ready to bid guard the yellow-colored

sheets like they hold all the secrets of the human soul.

Keith

Kantrowitz works for Power Express Mortgage Bankers in Great Neck

and is a regular attendee at the foreclosure auctions. "I'm basically

out here today looking to finance buyers," he says. "That's what

my company does. The auctions are a good place to meet potential

customers. Once in a while we buy."

A

few minutes later the bank representative and referee show up

and are immediately surrounded by anxious bidders. The first lot

up for sale on this day is a modest one-family home at 5615 Avenue

I. The referee, Barry Elisofon, reads a litany of rules that basically

warns buyers that the property about to be auctioned is being

sold in "as-is condition." The bank's representative starts the

bidding at $24,000. It quickly jumps to $125,000. Keith Kantrowitz

and a middle-aged Guyanese man in a flannel shirt get into a bidding

war. "$135,000," Kantrowitz drones.

A

moment of thought. "135,500!" counters the Guyanese man, folding

his arm across his chest.

Kantrowirz

smiles and ups his bid to $138,000. The referee looks around and

says, "138 going once, 138 going twice " He pauses and takes a

breath, "138,000, sold!" Kantrowitz, the referee and the bank's

representative go through the revolving doors of the courthouse

to sign the terms of sale.

"He

says he's out here looking for customers, and then he outbids

me on this house," says Safi Naziemul, the Guyanese man who is

looking to buy some new properties to fix up and sell. Properties

are listed in the Yellow Sheet, but buyers can only look at the

exteriors of places that are up for auction to determine their

condition. Some homeowners, angry at losing their homes, trash

the insides of their houses, requiring thousands of dollars in

repair. The interior configurations of the homes-the number of

bathrooms in a building, for instance-are also a mystery to the

bidders on the courthouse steps. It's a decidedly risky business

for an outsider.

"It's

tough out here. I think a lot of guys are in this together. You

see them on their cell phones constantly talking. You're up against

the banks and brokers," says Naziemul, "who are killing off the

small buyer by bidding so high."

The

action picks up again a few minutes later, with the auctioning

of a one- family house on East 32nd Street. A statuesque middle-aged

woman shows up as the referee and starts checking in the bidders.

A long bidding war breaks out between two Italian men; eventually

one of them gets it for $160,000.

The

owners don't usually show up to the auctions. "When an owner shows

up, it's almost like they don't believe that they're really losing

their homes," says Higgins. "When I explain it to them, I can

see their faces dropping as the reality sinks in. You see more

crying than anger, although if they get mad at anyone it's at

the referees because they're the ones who announce the sale."

Another

auction begins a few minutes later, and the regulars crowd around

a new referee. Standing off to the side, unnoticed by all the

bidders, is a heavy-set Jamaican woman clutching a Judgement of

Foreclosure. She looks helplessly at the proceedings as her house

is sold out from under her. When the referee announces the winning

price, she sighs. "I don't understand any of this," she mutters,

walking slowly back down Adams Street.

Originally

Published: August 1998 in B R 0 0 K L Y N B R I D G E

For information, log onto Web site at www.nyforeclosures.com.

© Copyright 2004 by

Buyincomeproperties..com